Regular readers will know by now that English Civil War portraiture is my ‘thing’, and as as result I have, over the years, created an impressive (if slightly nerdy) personal database of pictures from the mid 17th century, in an attempt to make sense of exactly who was painting whom, when, and sometimes, why.

When I first began researching, most pictures were listed as by an unknown artist, by the British/English School, ‘after Van Dyck’, or, in far too many cases, dumped in the pocket of either William Dobson or Robert Walker, the attributor being too lazy to search any further for another name. Yet in trying to catalogue these images, alongside the hundreds of unknowns, I have found over 25 named painters (so far), some well-known and foreign, others British natives working in their own small village or town, with only a single work attributed to them today. Clearly art didn’t stop because of the war, and while a vast number of canvases are of those directly involved in the conflict – armour-clad soldiers, courtiers, royalty, MPs, etc – there were still plenty of domestic, more personal portraits being produced in spite of it. Of course, even in wartime, life goes on.

If I had a time machine, I would use it to hunt down artists of the past, and sternly suggest they sign their portraits, as well as write somewhere on the back who their sitters were. How much easier our research would be today! Sadly, in the absence of such technology, we are left with countless orphaned canvases, their sitters almost mocking us as they look out from the paint, as if to say ‘well, I know who I am! You work it out!’

And so we try. Occasionally we have a clue, perhaps in the provenance, an inscription on the frame, or a passing reference in an old art book, but at other times there is very little to go on.

Take this gentleman, for example.

I found him on an online auction site, the short biography describing ‘A MID 17TH CENTURY ENGLISH HALF LENGTH PORTRAIT Of a gentleman wearing a lace collar and black silk tunic, contained In a heavy gilt frame. (69cm x 81cm) Condition: good‘. He could do with a decent clean, and the provenance would have been lovely had the seller provided it, but at present, he remains only an unknown man in black, painted at some time around the period of the Civil Wars.

Or this lady, also unknown, attributed to someone of the ‘British /English School’ – an easy go-to label given to countless other orphans – but at least in safe hands in the National Trust collection at Lacock, Wiltshire.

Then there are the ones that tease us with multiple names, convoluted histories or old assumptions that serve only to confuse us even more. We’ve previously discussed Sir Charles Lucas, and the countless paintings that have come to auction over the last 400 years carrying his name. Given that there is only one portrait commonly acknowledged to be of him, and of which none of the others shares even a passing resemblance, it illustrates the difficulties modern historians have, not only in the pure research of digging into archives or catalogues to identify a sitter/artist from physical records or factual documents, but also having to first wade through the layers of flat-out nonsense people have written and repeated over the centuries, that only serves to obscure the truth.

An example of this comes from the gentleman below, a Dobson work, currently residing at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. (Visit! It’s a great day out!)

He has been variously described as a Royalist (as at the NMM), a Royalist officer, a maritime commander, a man in a pink shirt, and of course, inevitably, Sir Charles Lucas.

So what DO we know? The props usually provide a clue as to an occupation. Armour might suggest a soldier, while quills, ink and paper can show an academic, or perhaps a writer or publisher. This man carries a sword and a blank piece of paper, and stands in front of an allegorical female figure holding a globe and dividers, common symbols for the sea, used to represent a sailor or traveller. It’s been argued that the paper he holds might be his naval commission, or perhaps a sea chart. The globe is taken to mean he must have served on the water, and even the blue material draped over his left arm signifies, to some, the colour of the sea.

Yet look again and it’s not so simple. The paper is blank. It could be anything: a private letter, or a note of introduction for our man to present overseas. People other than sailors travelled the world: merchants, diplomats and private businessmen. And does he look like a man who worked at sea?

A discussion about his identity can be found on Art UK’s Art Detective site, where it is suggested he could be a diplomat, the watery clues pointing to a man whose business was across the sea, rather than on it. I lean more towards this ambassador theory and hope the discussion continues, as I’d love one day to see his true identity added to the frame.

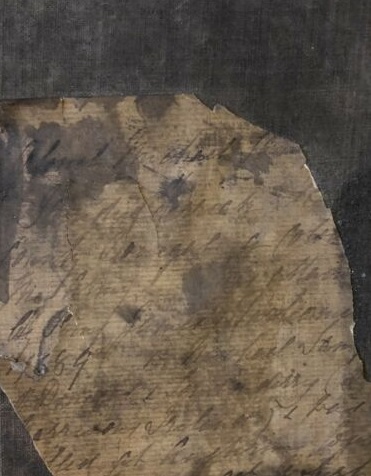

Finally, another that popped up on an auction site, in a very sorry state.

Bizarrely, this has been traditionally identified as a young King Charles I, and while I don’t think anyone who has ever seen a portrait of the King would believe this is him, it does illustrate yet again how messy the task of identifying a painting or artist can be. In this instance a big dose of ‘buyer beware’ should be applied before purchasing such a work purely on the basis of such a questionable attribution.

Yet even if we aren’t in the presence of royalty, we still have a very interesting painting. Who could he be? Excitingly, here is where my nerdy database may be of use. Although the paint is badly cracked and probably filthy, on first viewing our man he reminded me of one I’d already catalogued (source: http://www.historicalpaintings.com). The two paintings are, in my view, not dissimilar in composition.

What do readers think?

7

7